Every December we shove other responsibilities aside and spend hours at the puzzle table, solving the problems of the world. It starts the weekend after Thanksgiving, when we smush furniture around to make room for the table and the Christmas tree, which is a cozy alternative to how we smush things around in the summer, when we have birds living in our bathroom for three months of the year.

(Sidenote: You may be progressing in your homesteading efforts if a friend visits and exclaims, “Oh! I’ve never used your bathroom when it didn’t have quail in it!” So fancy.)

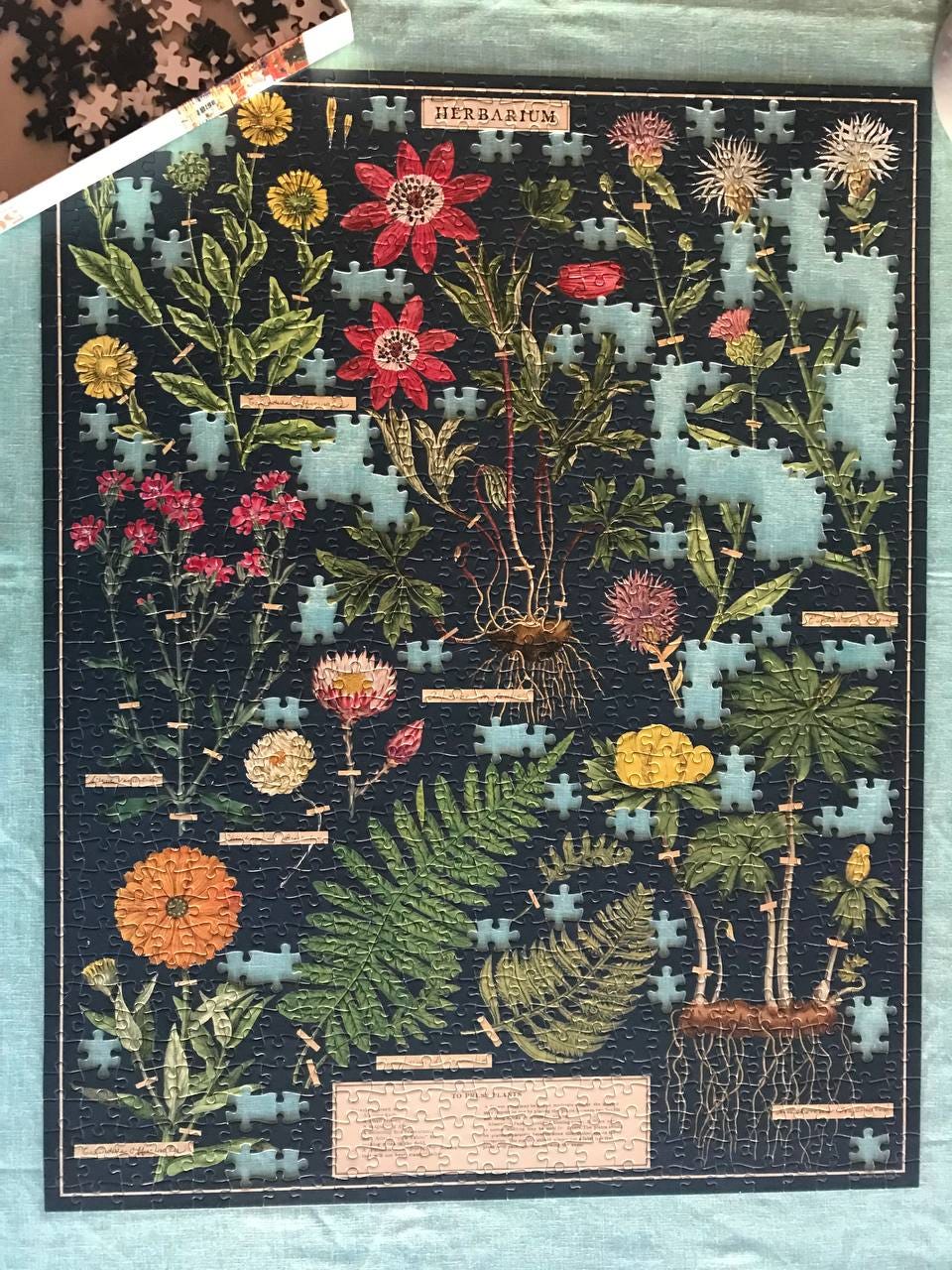

This last puzzle was difficult because at one point we had sections that started to connect from one side to the other, but there were odd gaps in one direction and tight spots on the other where the frame had warped a bit. We knew the pieces should fit, we just couldn’t figure out why they wouldn’t.

At one point I wondered if it was just a bad puzzle. There are some, you know – badly constructed, impossible to solve, and you only find out once you’re about halfway through. Then you have to decide if you’re going to keep going, or toss it and start over with something else.

Also, with pretty much every puzzle, there comes a point when I’m totally confounded and convinced that a certain piece must be a mistake because it has nowhere to go. This has to be a stem, but all the stems are finished…this one has to be a yellow flower, but there aren’t any yellow flowers left…we check and recheck, convinced the maker must’ve made a mistake and somehow this piece, which obviously doesn’t actually go with this puzzle, somehow got slipped into this box by accident.

But eventually, always, we find the place. OHHHHH, we exclaim as it clicks in, eureka. Suddenly it all makes sense: We couldn’t find it because we thought it was this color but it was actually the shading of that color, or we thought it couldn’t possibly attach and go there because of the lines in the drawing, but the cut of the jigsaw hid the transition from the stem to the leaf, or the edge where it changed from petal to background.

So as we sit here and exchange the pieces that confound us, we are recognizing more and more that what we think we’re looking at is sometimes not what it seems. We have the big picture but miss the small detail – or just as often, we have the small detail but miss the big picture.

Our work here, solving all the problems of the world, happens in small increments. With the puzzle that buckles, we have to make tiny shifts, move just a couple pieces at a time. It is gentle, steady work to make room for the sections that are supposed to fit.

We’ve tried it the other way; when we pulled the whole thing, sections tore away from the tension.

But there’s a thousand pieces, and so much needs to move, we think. Changing it all at once doesn’t work, though. We make room and move the loose, extra pieces out of the way, and it’s grace here, gentleness there, self control where we want to force our way…and we move a couple pieces at a time, realizing that tiny moves are the best influence on the big picture, because our forceful moves create disaster.

So this is a patient dance, one step here, one effort there; it helps to recognize every tiny victory, and overlook many forgivable imperfections. Our pieces need to shift and make room for each other, because there’s a gap here, and the space between is too big to fill. And that makes sense, because on the other side there’s not enough space for the other pieces that need to go in.

Washington had spent long hours talking to the officers, showing patience and tolerance, probing their sensitivities, hearing their complaints. It was subtle, had to be, the slow tilting of the level ground about which the men had so much pride.

As the officers themselves began to understand how they fit into the larger army, they began to have pride in their own units, in the behavior and deportment of their own men, in their own ability to command. They began to understand how discipline was of value after all, not just for convenience, but for each officer’s own value to the army.

– Jeff Shaara, Rise to Rebellion

On the other side of the table, Finn is sitting at the couch with a Rubik’s cube and confesses that he has solved it by peeling its stickers off and putting them back where he wanted them to go. I admit this is also how I’ve sometimes dealt with problems I couldn’t solve: We take the broken pieces and superglue them back on so everything looks fairly normal, as long as you don’t get too close and realize what a patch job it is.

But eventually, hopefully, there comes a time when we’re sick of the easy fix that was never good enough, and we want to be done with our inadequate coping skills. We want the real solution, and the real solution is always the work that needs to be done in us, not others, because it is inside us that all of our misperceptions and assumptions are made, our attitudes are born, our wounds are infected, and our potential for joy is hidden, however it is buried under difficult circumstances.

We need real healing, real freedom, and we’re willing to go through the pain or revelation we’ve been avoiding to face the One who knows how to put us back together the right way, because He’s the one who made us in the first place.

And this is where small moves will never be enough, because we’re no longer dealing with other people – I mean, external pieces – but with our own inward parts. Our own tiny efforts err in too much gentleness as we resign to just live with it and deal, and that can go on for a long time, maybe forever, unless we get impatient and move to the other extreme, creating disaster.

So we cannot do the effective work on our own pieces all by ourselves. When we’re broken enough to want real healing, we need to surrender to the Maker familiar with the big picture and all the details, who knows how our inward parts work, where the jigsaw needs to cut, and where all of our pieces go.

There’s a character in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader who, through a series of circumstances and bad choices, becomes something unexpected. He needs healing and he thinks he knows how to go about it, so he starts to cast his skin:

“I scratched a little deeper and, instead of just scales coming off here and there, my whole skin started coming off beautifully….But just as I was going to put my feet into the water I looked down and saw that they were all hard and rough and wrinkled and scaly just as they had been before.”

Like we often discover, our own efforts don’t go deep enough. So we try the same thing, harder:

“Well, exactly the same thing happened again. And I thought to myself, oh dear, how ever many skins have I got to take off?”

Eventually, depending on how stubborn – or evasive – we are, we realize the truth: We can’t do this. He has to be the one to heal us. And this is where surrender happens.

“The very first tear he made was so deep that I thought it had gone right to my heart….he peeled the beastly stuff right off…and there is was lying on the grass: only ever so much thicker, and darker, and more knobbly-looking than the others had been. And there was I as smooth and soft as a peeled switch and smaller than I had been.”

– C.S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

He cuts our wrong edges off in precise curves, not taking anything that needs to stay and not leaving anything that needs to go. But He doesn’t do it the same way in each of us.

A few weeks ago in class we talked about how God moves us in surrender. For the chatty extrovert, sometimes surrender looks like waiting in uncomfortable silence; for the introvert, it looks like reaching out to the person who is new and starting a conversation. For the impatient mom, it looks like listening to the angsty rant of a teen rather than immediately giving the answer. For the overindulgent mom, it looks like setting a boundary and holding to it.

Whatever it is, overcoming our preferred comfort is how we die to self to become truly alive, and it’s the surgery we need, revealing the tender, raw perfection of His design underneath.

Our own vulnerability makes us walk more tenderly toward others. Simultaneously, as we realize how efficient His work is, it makes us want to surrender our stubborn ways faster, and we move in bolder freedom than ever before. Surrender is a cycle that continuously strengthens.

We cannot do the giant work in others. Our own efforts aren’t even enough to do the perfect work in ourselves. All we can do are the small everyday steps of obedience, finding where this piece goes, sorting out those other pieces, moving loose pieces out of the way so there’s room for the right ones to go in.

So we lay it all on the table – the pieces we think we know what to do with, the ones we have no idea what they’re for, and the ones we’ve been hiding in our pocket so no one else could touch them.

It’s all out there. The picture is coming together. We sit in the tension of seeking answers until we have the aha moment when it clicks, and we finally see it the way the Maker does — the details, the big picture, everything in place — and we unbend our twisted frame back into His alignment, making room for all the pieces He designed to be there.