This, like last Saturday’s news, is not about political parties or an election. This is about a fight for our culture.

Last week’s assassination attempt was meant to do more than kill one man, which is horrific enough; we need to recognize that that man was not the only intended target.

Every American watching on live TV – plus those who would see the videos replayed ad nauseam in the future – was a target, because it was intended to horrify and traumatize every witness: Not just those attending the rally, but every man, woman, and child who watched, live, with cameras rolling.

All were meant to see the gore and blood and terror.

And it was meant to be replayed and replayed and replayed until all were desensitized to the horror and it became ho-hum in our culture.

So this was a message, too: Don’t threaten the status quo, and stop fooling yourselves about how “free” you are. Just so you know, this is what happens to people who threaten those in power.

Some of them will do whatever it takes to stay there.

So yes, we are under attack. There are people who want to make our everyday activities a war zone of fear and panic – and if that strikes you as hyperbole, you’re just not paying attention.

I “just happened” to be reading about another attack this week – in a less dramatic way than Trump “just happened” to turn his head at the pivotal second, but the source of both moves was the same, no doubt – and have been praying through its lessons all week.

It’s one of the most famous battles in the Bible so you’ve probably read about it and heard it mentioned in a hundred sermons before. But there’s good news for us here, and it, too, takes place after there has been exposure of evil, followed by government reform:

After this [King Jehoshaphat’s reforms] the Moabites and Ammonites, and with them some of the Meunites, came against Jehoshaphat for battle. Some men came and told Jehoshaphat, “A great multitude is coming against you from Edom, from beyond the sea; and, behold, they are in Hazazon-tamar” (that is, Engedi). Then Jehoshaphat was afraid and set his face to seek the Lord, and proclaimed a fast throughout all Judah.

– 2 Chronicles 20:1-3

The first part of this last sentence is key because two things happen in conjunction that don’t always go together:

1) Jehoshaphat felt afraid, and 2) he sought the Lord.

Wait, why is that weird? Isn’t that what we’re supposed to do?

Yes, it is. But it’s not what we always do when we’re afraid. We know it’s what we’re supposed to do, but that’s totally different.

What tends to happen when we’re afraid? Often we panic and look for the obvious answer rather than seeking the Lord (we see this throughout the Bible, too). Alternatively, sometimes we feel shame immediately after fear because we know we’re not supposed to be afraid, and that drives us from the Lord too, because shame is a separator.

But Jehoshaphat didn’t fall for those. He did the right thing, sought the Lord, and led his people in doing the same thing, per verse 4:

And Judah assembled to seek help from the Lord; from all the cities of Judah they came to seek the Lord.

Then King Jehoshaphat prays. And as he recognizes who God is and what He does, he’s also reminding himself and his people:

And Jehoshaphat stood in the assembly of Judah and Jerusalem, in the house of the Lord, before the new court, and said, “O Lord, God of our fathers, are you not God in heaven? You rule over all the kingdoms of the nations. In your hand are power and might, so that none is able to withstand you.

He continues: You cleared the land for us. You gifted it to us. We’ve lived here and made a sanctuary for Your name, and remember? Ages ago, back when the Ark was brought into the Temple and Solomon prayed, we made a deal together: If disaster comes, and we cry out to You, You will hear and save us. And here we are, under attack.

Then he says this:

O our God, will you not execute judgment on them? For we are powerless against this great horde that is coming against us. We do not know what to do, but our eyes are on you.”

– 2 Chronicles 20:12

There they stood, like we do, with their families: husbands, wives, little ones. Waiting. Wondering what to do. Knowing that anything we can do on our own is just a drop in the bucket, so futile without God’s help.

And then the Spirit comes.

And through Jahaziel, a man who is never mentioned anywhere else in the Bible, He speaks:

And he said, “Listen, all Judah and inhabitants of Jerusalem and King Jehoshaphat: Thus says the Lord to you, ‘Do not be afraid and do not be dismayed at this great horde, for the battle is not yours but God’s. Tomorrow go down against them. Behold, they will come up by the ascent of Ziz. You will find them at the end of the valley, east of the wilderness of Jeruel. You will not need to fight in this battle. Stand firm, hold your position, and see the salvation of the Lord on your behalf, O Judah and Jerusalem.’ Do not be afraid and do not be dismayed. Tomorrow go out against them, and the Lord will be with you.”

– 2 Chronicles 20:15-17

Isn’t that nice? I mean, the Holy Spirit was right there telling them exactly what to do, where to go, and what would happen.

That would sure be handy for us right about now, too.

But what if He has already told us what to do?

What if we just need to be focused on those things? And rather than apologizing for how insignificant they seem, what if we realized how powerful they are?

To sum up, let’s look at their instructions:

Do not be afraid. There it is again.

Do not be dismayed. Not the same as fear; more like “disillusioned” or “discouraged.”

Okay, those are the things we don’t do. Got it, easy peasy…riiiiight.

But now, for the things we do:

Go meet them tomorrow, stand against them. On the offense, not the defense. And this is interesting because I was just looking at this other passage recently:

For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places.

— Ephesians 6:12

Ready for some Fun With Greek? Of course you are, yay!

The repeated use of the word “against” struck me in this verse. The Greek word is “pros” and some translations use the word “with” (“we wrestle with the rulers” etc).

But it means a motion TOWARD something to interface with it. It’s not defensive, but offensive — we are to make the move forward, against, toward the threat, not simply to stand where we are and hold our current ground.

We offensively oppose the spiritual forces of evil — pressing forward and even plowing over (or through) enemy ranks.

So we’re looking at two different instances of “standing against” in Scripture: One in Hebrew and one in Greek, but both are in the context of battle.

We do not step back and diminish anything we’re already doing. We don’t cower or cave or shrink; we take what we have and press onward, against the threat. We don’t give the enemy room; we take the land and make him shrink back. We don’t give ground; we gain it.

We do not turn down our volume or our voices or our beliefs. We destroy strongholds, arguments, and every lofty opinion raised against the knowledge of God, and take every thought captive to obey Christ.

And then we see this final instruction:

Stand firm, hold, and watch the Lord save you.

If you know this story, you know Jehoshaphat and his people ended up battling through worship. They fell down in worship, stood up in praise, and they weren’t quiet about it. And when they did that, the Lord set an ambush against their enemies, so that they were routed.

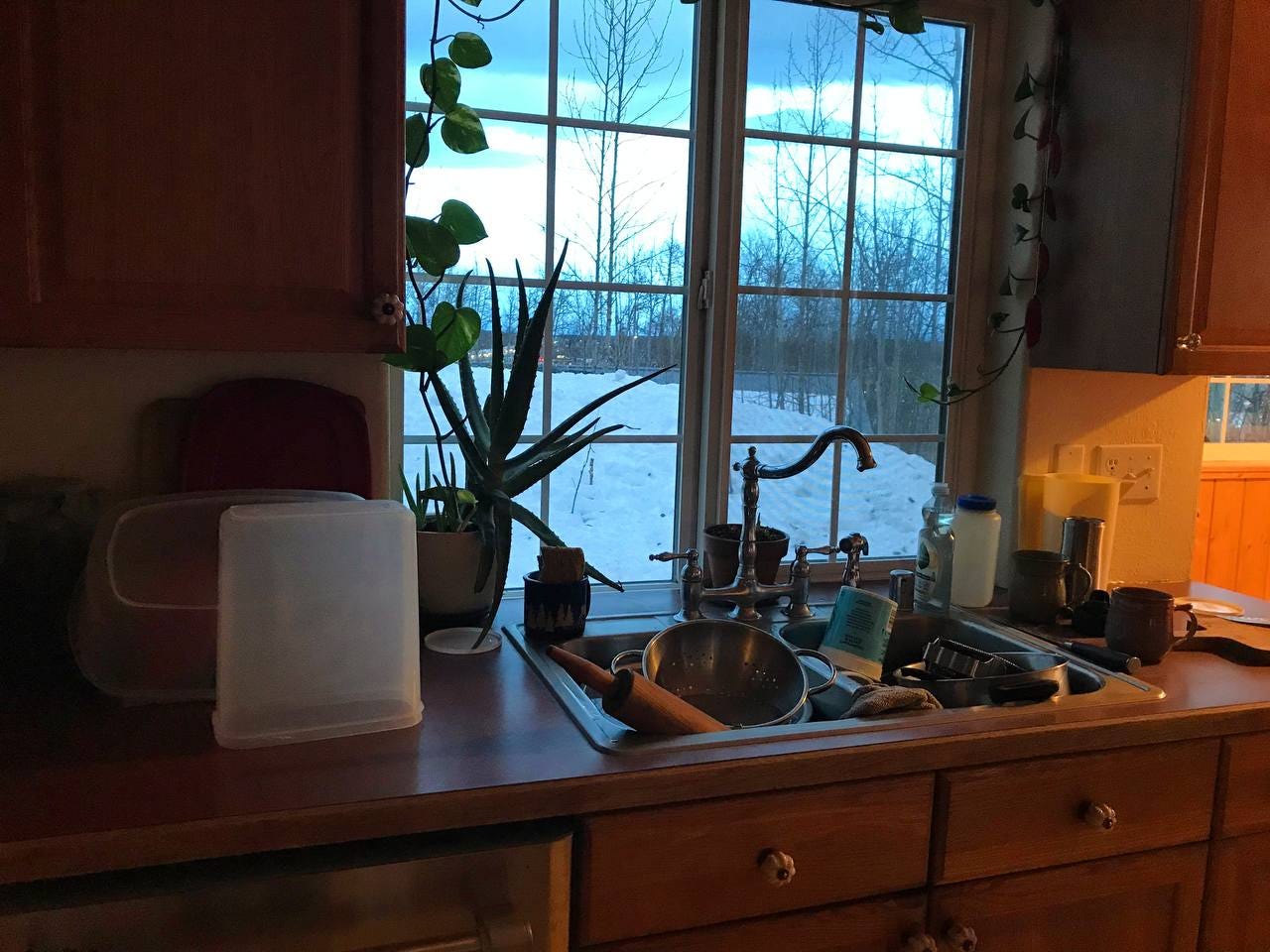

The daily small things we do are notes in the song as we march our days forward: making these sandwiches, learning this skill, memorizing that verse, reading those books with the kids, having that talk with a friend. We will not cede this ground; we will not live in terror; we will not let our children grow to know a country that is less than what we ourselves were raised in.

We will not be intimidated into shrinking silence and survival mode, pursuing safety over sanctification, choosing the idolatry of living in fear of man.

We will live in loud freedom, instead.

They set a net for my steps; my soul was bowed down.

They dug a pit in my way, but they have fallen into it themselves.

My heart is steadfast, O God, my heart is steadfast!

I will sing and make melody!

Awake, my glory! Awake, O harp and lyre!

I will awake the dawn!

I will give thanks to you, O Lord, among the peoples;

I will sing praises to you among the nations.

For your steadfast love is great to the heavens,

your faithfulness to the clouds.– Psalm 57:6-10

Our steady, life-giving routines are the chorus we keep coming back to: Turn this page in the Bible and move on to the next chapter. Pray with your spouse, pray with the kids. Weed the garden, harvest the veggies, delight in the flowers blooming. Make the meal, gather with friends. Take something to the neighbor, pick up the trash along the road. Call your grandparents, or your grandkids. Chat with the grocery clerk you see every week.

For our boast is this, the testimony of our conscience, that we behaved in the world with simplicity and godly sincerity, not by earthly wisdom but by the grace of God, and supremely so toward you.

– 2 Corinthians 1:12

Seek the Lord, and assemble, because of the increase of his government and of peace, there will be no end.

The Kingdom is here, at hand, all around us and within us. The Kingdom is peace, joy, and righteousness, and every move to abide and reflect Jesus makes earth a little more as it is in heaven.

God is setting an ambush and routing the enemy as the Word reigns in and around us. That Word hovers through the land as we read, sing, remind, write, recite, and declare.

We don’t need to be on stage; we’re all leading worship.

All were meant to see gore and blood and terror, but instead, we witnessed a miracle. And singing and rejoicing as we take the land, we will continue to do so.

Subscribe here to get my posts straight to your inbox. And if you liked this post, you might also like these, too: